HUMAN FACTORS: THE GROUP

MOST FIRST-HAND ACCOUNTS REVEAL THAT THE CAUSES OF AN AVALANCHE MORE OFTEN THAN NOT DERIVE FROM HUMAN FACTORS AND GROUP DYNAMICS RATHER THAN A POOR ASSESSMENT OF SNOWPACK STABILITY. TRAVELING THROUGH THE SNOW-COVERED MOUNTAINS MEANS MANAGING A CONSIDERABLE AMOUNT OF UNCERTAINTY, WHICH REQUIRES SKIERS TO MAKE DECISIONS BASED ON RELIABLE, PROVEN METHODS, AS WELL AS GOOD COMMUNICATION SKILLS.

When preparing for an outing, it is important to assess each individual as well as the group as a whole.

- How many of us are there?

- What are everyone’s level of experience and skills?

- What types of personalities do I have in my group?

- Does everyone in the group have similar experience and skills, or are their considerable disparities?

A group made up of people with similar experience and skills is easier to manage than one where there are huge disparities. The outing should suit the level of the group, especially the person with the lowest skills and level of fitness. Plans should also fit with each individual’s expectations. To avoid any frustration or disappointment, everyone in the group should agree upon where to go and contribute in some way to planning the outing.

Technical skills, fitness, and overall experience and knowledge count a great deal towards staying safe. However, avalanche risk experience is difficult to acquire. The backcountry is just too uncertain to gain experience being near or caught in an avalanche. You can spend years making poor decisions and travel near or even across terrain in extremely unstable snow conditions without ever being caught. Finishing an outing “safe and sound” does not necessarily reflect upon good decision-making skills or mean that you made the right decision at the right time.

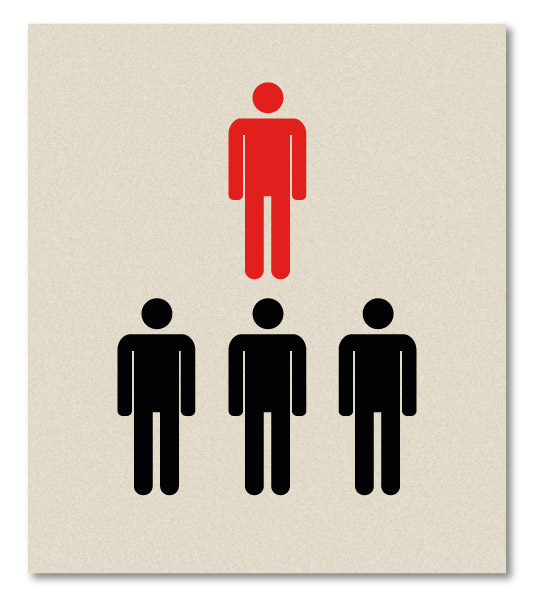

The leader ensures good communication within the group, confirms group decisions, and provides instructions about proper conduct within the group and during the outing. Their role is to identify key decision-making moments. The other members of the group still need to participate in managing the risks by communicating their observations and ideas as part of helping the leader make a decision. In general, the leader is the most experienced person in the group but their ability to clearly communicate needs to be taken into consideration.

No clear leader = no clear group communication no clear group management, no clear guidance over the course of an outing. This is often the case with a group of skiers and/or snowboarders who have the same skills and experience without a designated leader. They may continue to push the envelope until an accident occurs since this configuration is not conducive to clear communications or creating an atmosphere where group members feel comfortable speaking up when they observe one or more obvious signs of danger.

A study by Ian McCammon revealed that the social connection between the individuals in a group influences the decision-making process. This individual behavior can lead to an accident. Heuristic traps such as “Acceptance” and “Social Facilitation” often lead to wanting to impress one’s peers and increase risk taking in spite of the clear warning signs that danger lurks ahead. The individual commits to a project or plan ill-suited for their skill level, experience, or fitness level simply to please or to prove themselves to others in the group. These traps are observed more often with groups that include both men and women (a higher accident rate).

When tired, we do not use the “reasoning” part of our brains. Our subconscious, which consumes much less energy, kicks in over “reason”. Fatigue therefore does not facilitate well-reasoned decision making, and encourages risk-taking by giving way to the easiest choice. Even if a slight detour would be much safer, fatigue incites us to take shortcuts, to take the easy way out. “Is our tired state influencing the decision we plan to make?” is the right question to ask to make the right decisions.

The mental aspect should also be taken into consideration. If the decision maker is distracted by personal problems, the decision as to where to set the uptrack or where to descend may be compromised and lead to making the wrong choice or even an accident. Do our worries and personal problems influence the decisions we make? These questions should help when deciding whether or not to change the originally planned itinerary.

One’s state of mind, the desire to impress, or the overall excited mood of the group can potentially lead to peer pressure or inflexibility with regard to the objective and wanting to reach it. A group that wants to reach the objective at all costs will only look for information that reinforces their original decision without taking into account any obvious warning signs or hazards. This irrational choice can prove extremely dangerous.